Tilting at Statues

Notes on an Ever-Present Past, Part 2

American Anti-Racist Protests Go Global

In the days and weeks after the murder of George Floyd, protests emerged around the world. In many European capitals (Berlin, London, Copenhagen, Helsinki, Dublin, Reykjavik, and others) thousands of protestors marched in support of the notion that more attention ought to be paid to contemporary racial inequality.

Interestingly, many of these protests centered around monuments to racist figures of the past. In Ekeren, Belgium, protestors graffitied and burned a statue of King Leopold II. In South Africa, a bust of Cecil Rhodes was decapitated. In Budapest, a bust of Winston Churchill was defaced (unironically, it seems) with the word “Nazi.” A statue of Voltaire across the Seine from the Louvre was the target of repeated acts of vandalism (it has been removed for rehabilitation).

The toppling of one monument in particular caught my attention. In Bristol, England, protestors took down a statue of Edward Colston and then unceremoniously dumped it into Bristol Harbour. Colston was a 17th-century merchant who became fabulously wealthy by trading, among other things, human beings.

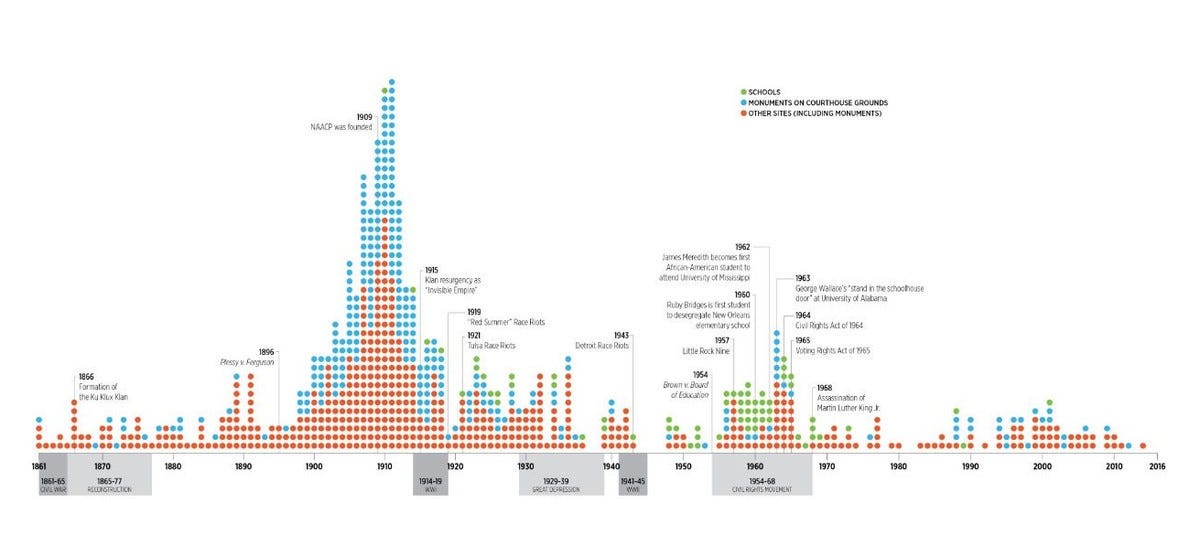

What intrigues me about the Colston statue is the way it differs from the Confederate monuments in the US that have been the object of activists’ protests. The Confederate monuments were erected specifically to honor those who fought to continue the institution of slavery. Furthermore, they were largely erected during the backlash to Reconstruction and the Civil Rights Movement as a scare tactic.

Colston’s statue, by contrast, was erected to celebrate his philanthropy. Colston donated money to a whole host of institutions in Bristol, and his philanthropy was so exceptional that it inspired other merchants, unrelated to him and from later eras, to set up their own philanthropic societies in the mold of his. An inscription upon his death referred to him as, “the brightest Example of Christian Liberality that this Age has produced both for the extensiveness of his charities and for the prudent regulation of them.”

This is not a paean to judge figures of the past only by the norms of their own era. Nor, however, ought we to judge them exclusively by the norms of our own. Any attempt to fully understand past figures must wrestle both with who they were within the context of their own eras as well as how we might subsequently judge even “the brightest example of Christian liberality” of his own era today.

Contemporary society is the result of people, ideas, and institutions bequeathed to us from an abidingly complicated past. Few figures are Hitlers or Christs. Even fewer institutions are so purely evil or good. For historians, more nuance, context, and contingency can help expand our understanding of the past. But for the rest of us, our task is to make a better present and a better future. To this end, the ever-present past can often stand in the way.

Why monuments?

The focus on monuments to historical figures in the name of contemporary advocacy for a more equal society may at first seem curious. Why, if the goal is ending racial inequality in today’s society, would such historical figures become centerpieces of resistance? It’s my belief that this focus arose out of the contemporary discourse via a successful attempt on the part of the right (and, at times, center) to bog down activists in fighting battles of little consequence.

We might pause for a moment to consider the focus on symbols of racism as sites of protest. Monuments, statues, and buildings named for historical figures aren’t doing racism today, but they are symbols of racism in a still-racist society.

Historical figures are actually somewhat ancillary to activists’ initial claims. Contemporary social justice advocates note these monuments to the Confederacy as a sort of metaphorical QED tacked onto the end of observations about society’s contemporary inequality. They’ll note gaps in wealth or education or power between white and black Americans, observe that this suggests something about the country’s endogenous racism, and only then cite the existence of schools named for Robert E. Lee as the sort of “see…”

It is because contemporary racism is harder to pin down than the racism activists fought in the past that these symbols become gathering points for protests. Lunch counters refusing to serve Black patrons made them an obvious target for protests. Such institutions, owned by white people, run by white people, executed policies (carried out by white people) that were explicitly racist. Everyone could see it. There were big signs that said “whites only.”

Today’s racism is more insidious. In today’s America, there are legal prohibitions on explicitly racist policies like redlining, meaning that the contemporary policies that perpetuate racism are all at least facially neutral. Addressing contemporary racial inequality thus requires greater focus on the racist-in-effect-but-not-in-language self-sustaining systems like the flow of inter-generational wealth à housing à schools à jobs à Income à wealth1. But these complex systems are intangible. In what physical location can we witness the act of racism at the core of these systems? It is hard to locate. The monuments then, although not central to activists’ point, serve as the physical proof of society’s otherwise intangible collective racism, making them at least fitting symbolic locations as sites of resistance.

From here, some right-wing racist provocateurs will suggest that “well, actually Lee wasn’t so bad,” or “well, actually, it’s reasonable for people to erect a monument to the Confederacy 100 years later,” or “well, actually, the Civil War wasn’t about slavery,” which sort of compels activists to rehash the point that 1) contemporary society is still racist in many ways and 2) these historical figures were racist in many ways.

This back-and-forth between social justice advocates and right-wing provocateurs is then described by centrist observers2 as “disagreement” or “different perspectives.” Centrist liberals who seem most interested in portraying themselves as “very reasonable people,” have (some accidentally, some nefariously) bought into the idea that social justice advocates arguing about the degree of immorality of historical figures is evidence of “cancel culture.”3

Hospitable as I am to activists’ aims, and right as I think they are about not naming monuments, places, etc. after evil people of the past, I do think this back-and-forth has also bamboozled some of them. They feel the need to win the fight over history, but winning the argument about the past doesn’t necessarily make anyone more willing to remedy present injustices. “That person you admire was actually bad” is, unsurprisingly, not an effective argument for any sort of prescription to ameliorate today’s injustices.

I don’t totally blame the activists for this. They are confronted on the one hand by a bad-faith openly-racist illiberal right-wing cabal intent on preserving white supremacy anyplace it can be found and on the other hand by people whose very sense of self is finding the midpoint between two supposed “extremes.” The latter group’s intentional misinterpretation of what this whole debate is about lets contemporary people and institutions doing ill off the hook. More insidiously, it allows some institutions to purport to be justice-seeking for remedying past wrongs while continuing to perpetuate contemporary ills.

Harvard’s Focus on Past Wrongs

Harvard recently followed the centrist playbook perfectly. For some time, those on the left have been pushing for Harvard to be a more progressive institution. The critique of contemporary Harvard tends to focus on its status as an institution that reinforces social hierarchy. Old-money parents send their kids to Harvard to ensure they maintain their status among the American aristocracy. The best prescriptions for ameliorating this focus on things like expanding access to a Harvard education (literally, just admit more students) and ending legacy (and donor) preference in admissions (this is a no-brainer).

Like many other powerful institutions, however, Harvard has self-servingly chosen to misread racial justice advocates’ critique while trying to appease them. The critique, as with all of the focus on history and monuments, is not about the historic injustice per se, but rather that the failure to acknowledge and atone for such past injustices is one among many signals that the institution remains an obstacle to the goal of a more just society. But Harvard has chosen only to identify past (and long-ago past) failings as things it must investigate and redress.

Harvard’s PR operation this week was excellent. It had commissioned a report to examine its entanglements with racism. It had seen the report and prepared a response, and the response was what made headlines: $100 million! That sounds like a lot of money to commit to redress past wrongs.

But imagine, just for the sake of argument, that Harvard were able to track down the descendants of those enslaved (one of the tasks this $100 million is supposed to fund). The full cost of attendance at Harvard today is over $80 thousand/year. Let’s round up, supposing that such students might need additional supports than Harvard is accustomed to providing and say that the commitment would cost Harvard $100 thousand per year of education. If all the students they enroll graduate in four years, the full $100 million would fund a mere 250 students. In reality, the money is also budgeted to fund other things (more research, memorials, monuments, etc.) too.

Paying for 250 descendants of people enslaved by Harvardians of yore to attend Harvard is better than not doing so, but it fundamentally fails to address the ways contemporary Harvard is a barrier to a more just society. And while more charitable observers might choose to see the two things as unrelated (Harvard can both redress past injustices and present ones), I am more cynical. The two are intertwined, and Harvard’s focus on the past is designed to obscure its present wrongs.

Consider this passage from the report Harvard commissioned and published: “That universities continued to exclude or discriminate against descendants of enslaved people into the middle of the 20th century deepens their complicity with this history of oppression.” The report is willing to walk right up the brink without acknowledging that today’s institution remains racist. By presenting discrimination exclusively in the past tense, the report is explicitly presenting Harvard’s discriminatory entanglements with black people as a thing of the past.

Harvard is Still Discriminating

A closer examination of Harvard’s contemporary admissions policy, however, reveals that Harvard’s discrimination persists in other forms that continue to systematically disadvantage descendants of enslaved people (among many others).

Over past years, a series of right-wing groups have targeted Harvard with lawsuits alleging discrimination against Asian students in Harvard’s admissions policy. Asian students, they claim, have to perform significantly better on standardized tests in order to have the same chance of admission as other students (white, black, and Hispanic, specifically). The lawsuit has compelled Harvard to release detailed records of admissions decisions broken down by race of applicant, which, in turn, has allowed researchers to understand in detail Harvard’s admissions policy and how it impacts different groups of students.

The first point to distinguish is that there are multiple pathways into Harvard. The researchers who examined Harvard’s policies examined 4 alternative entry paths. These pathways were for athletes, legacies, dean’s choice (usually for children of donors), and children (of people affiliated with Harvard), collectively referred to as ALDCs, as distinguished from students who apply without some connection to the institution or having been recruited by a sports team.

Unsurprisingly, the ALDC students were likelier to be admitted, likelier to be white, likelier to be wealthy, and less academically prepared (lower GPAs/test scores) than the average admitted student. The acceptance rate for ALDC applicants is 30%, or roughly 6 times higher than the 5.5% it is for other students. 43% of white students enter Harvard via these back doors, compared with less than 16% of Black, Asian American, and Hispanic students. Moreover, the white students who get in via the ALDC pathways are suspiciously underqualified. Evaluators of Harvard’s admissions practices estimate that 75% of white ALDC admits would have been rejected if they were treated like other non-ALDC white applicants.

The continued use of ALDC admissions alone should totally undermine Harvard’s alleged commitment to redressing its legacy of slavery. It’s not just that Black students weren’t admitted in remotely proportional numbers until well into the 20th century, though this is a big part of it. It’s that Harvard recruits for varsity crew, squash, fencing, and sailing—sports even my extremely affluent suburban public high school didn’t offer. Harvard’s admissions policy is designed to get rich kids in the door; it’s not designed to be meritocratic.

The Harvard Outcome is the Modal Outcome

The outcome of Harvard’s investigation into its past entanglements with slavery ought to be a cautionary tale for social justice advocates. Bad-faith actors will abuse activists’ employment of history as a rhetorical point about contemporary society’s ills to either bog them down in debates about past wrongs or focus any contemporary change away from even the slightest disruption to the balance of power in the status quo.

I am not the world’s most cynical person about this. Upon his resignation as president of Amherst College, now head of the New York Public Library Anthony Marx lamented that elite higher education institutions are inherently and irredeemably beholden to the interests of the monied and powerful.

I disagree. Institutions are not inherently anything – they are changeable by the people who constitute them. It is certainly hard to effect change in definitionally plutocratic institutions (one buys one’s way onto the board of trustees at most universities), but it is not impossible. Trustees’ can be replaced or their minds changed. Policies can be revised or eliminated. Stakeholders (students, faculty, staff, alumni) can pressure the institution to make these changes.

At this point, however, I think activists are losing more than they’re gaining by bringing past injustices to the fore. We ought to know about them. We ought to understand how they impact contemporary society. But the argument for changing contemporary society and building a better future ought to be predicated on contemporary society’s ills.

Conclusion

In the wake of the toppling of the statue of Edward Colston, police superintendent Andy Bennett explained why the police hadn’t intervened to prevent the monument’s destruction.

“You might wonder why we didn’t intervene and why we just allowed people to put it in the docks – we made a very tactical decision, to stop people from doing the act may have caused further disorder and we decided the safest thing to do, in terms of our policing tactics, was to allow it to take place.”

We won’t find a better metaphor for the status quo’s attitude about the relationship of past and present. “We better let them tear down the monument or else they might push for more substantive change.” Presumably Bennett was talking about property damage to local business, but he may just as well have been talking about Harvard’s investigation into its past. Sacrificing the illusion of past virtue in exchange for a preservation of the status quo is a good trade for the powerful.

Contemporary activists ought to heed Bennett’s words. A focus on the past isn’t necessarily in the best interests of activists. A philanthropic institution named for Edward Colston disbanded. Many Confederate statues and memorials were removed. And Harvard is committing $100 million to who knows exactly what. None of these was really the goal (well, maybe removing, Confederate memorials was an ancillary one).

Those of us striving to make a more just, more equal society ought to lead with our aspirational goals, using history only when a critique of contemporary society is insufficient.

Instead of “Harvard needs to redress its history of racism and discrimination,” the argument should be, “Harvard must admit more low-income and underrepresented minority students to show it is an institution for all students, not just the children of the wealthy.”

Instead of, “the legacies of slavery and Jim Crow fuel contemporary racial inequality,” the argument should be, “reparations are necessary to ameliorate contemporary inequality that is the direct result of centuries of legal slavery and discrimination.”

History can be a guide for the present, providing illustrations of pathways to both success and failure. But a disproportionate focus on the past can complicate the battle at hand: confronting the forces that take the profoundly imperfect present as sacred merely by virtue of its historical provenance.

No matter how much we wish, the past cannot be changed. The good and the bad have already happened, and striving for unanimity in the interpretation of the past is a fool’s errand indeed. But we can change today and tomorrow by liberating ourselves from continuously relitigating the injustices of the past and just doing the work, cultivating our garden.4

It should be noted that there are still also plenty of one-off acts of racism (conscious or sub-conscious) from individual functionaries (hiring manager, store clerk, waiter, boss). These certainly add up in the aggregate both in the symbolic violence they inflict on minoritized people and in how they contribute to racial inequalities in the aggregate. But nor do these (except in truly egregious instances like police murdering of unarmed people) make for good sites of protest. It’s hard to protest an interpersonal slight, even when said slight was clearly racist in nature.

The linked piece, for example, includes the following quote: “But when the newly viralized social-media platforms gave everyone a dart gun, it was younger progressive activists who did the most shooting, and they aimed a disproportionate number of their darts at these older liberal leaders.” This is unsubstantiated anti-left drivel that’s designed to give Haidt the appearance of reasonableness. Imagine telling Jews and people of color on social media, people who get sent photos of their kids photo-shopped into gas chambers, that it’s middle-aged liberals who get the worst vitriol on social media. What utter nonsense.

No one, in my view, has been a more astute observer of “cancel culture” (which I put in quotation marks because it’s not a real thing) than Michael Hobbes. I’d encourage everyone to watch his 20-minute video on the subject here. It’s superb.

If you find yourself struggling to figure out how to evaluate the latest claim that someone did something bad a long time ago, I’d also refer you to my piece on the subject here.

Voltaire, far from an enemy of progress, was one of its greatest champions, and this was the metaphor for working to build a better tomorrow with which he closed Candide.