Behaving Ethically During a Pandemic

Our responsibilities to each other have changed; our goals should too

We are now over two years into the pandemic. Throughout that time, we have all had to repeatedly make many decisions with insufficient information and guidance. Is it safe to socialize outdoors? When should I wear a mask? Do I need a booster shot? Can I send my unvaccinated toddlers to day-care?

This decision-making has been complicated by government failures up and down the federalism spectrum. I wrote at length about what those failures meant for individual decision-making one year into the pandemic. But government organizations aren’t the only institutions floundering in this environment. Businesses are struggling too. What rules should be true for customers to enter their franchises? For their employees?

People and institutions have been trying to navigate this new more complex world for two years now, and we (both as individuals and institutions) have made some good decisions and some bad ones. But we find ourselves once again at a precarious moment. The push for a “return to normal,” is ascendent, and institutions are walking back mitigation efforts all while it appears a new surge of cases (in the US) may be around the corner.

Throughout the pandemic, the left has advocated more aggressive mitigation measures than the right. These have largely been valuable. But in recent months, as “back to normal” becomes the apparently dominant attitude, the left and the center-left are sniping over behavioral choices – whether it’s okay to not wear a mask or go to a restaurant.

I think there’s a logical explanation for why people are focused on individual behavior here: in the early days of the pandemic, everyone adopted the language of “we all must sacrifice to flatten the curve.” Today’s debate continues to be primarily about individual sacrifice. Instead, we need to focus on the policies that will help us lead flourishing lives amidst the continued scourge of a deadly disease.

The question of individual choice is still essential, and the first part of this piece discusses the importance of individual decision-making in the context of what responsibilities we have had to each other over the course of the pandemic. How have those responsibilities changed over the last two years?

The second part of this piece involves questions of institutions and policy-setting. How can institutions – and above all, government institutions – maximize the opportunity for people to do what they like while simultaneously not being subjected to risk of long-term health consequences or death?

The course of the pandemic wasn’t clear in May, 2020

In May, 2020, cases were coming down. It seemed possible that we were on the verge of achieving some sort of détente with the virus. It would spread, but at a volume that wouldn’t overwhelm the healthcare system or result in massive amounts of disease and death before the arrival of vaccines, which were already forecast for early 2021.

The default political position of the left became to strive for the lowest possible number of cases until (first) the level of cases came down to a level where contact tracing of all cases was possible (and second, when the first didn’t materialize) vaccines arrived. Democratic politicians didn’t always get priorities right (in some places restaurants were open and playgrounds were closed), but the general idea of, “stay home; save lives; re-evaluate once vaccines are available,” was sound.

The epidemiological reality driving this decision was that you might have COVID. Lots of people with COVID were asymptomatic. Other people who would become symptomatic were transmitting the disease before they became symptomatic. And there was not much one could do to protect oneself other than don a mask (which had been briefly discouraged by the CDC). We weren’t yet sure about how well different kinds of masks worked and high-quality masks were needed for healthcare professionals.

I felt the utilitarian calculus was obvious. On one side of the equation was an unknown but very large negative: lots of deaths. On the other side of the equation was a short-term cost: sacrifice ~12 months of many of the things that give life pleasure and meaning.

By isolating as much as possible, we ensured that the risks we did take (like going to the grocery store), had limited downside; should we become infected, we wouldn’t precipitate cascading chains of infections. In my case, because I wasn’t socializing indoors, the only person exposed to risk from my activity was my partner, and we basically took all the same risks.

An Honest Reckoning of the Costs of Isolating

When the calculus was, “stay home or risk killing lots of people,” the left, eager to win the argument against the death-cult of right-wing denials of the virus’s severity, attempted to minimize the costs of isolating. “At least it’s happening in the age of Netflix and the internet” was a sort of joke about it not even being that bad to stay at home. But it was!

Human interaction is what brings joy to life. We find meaning in our interactions with others. We find beauty in the world. We find perspective by changing our own. We find purpose in the way our own actions impact those of others. All of these were severely circumscribed by isolating.

Beyond the existential, there were purely logistical aspects of people’s lives that were made worse by isolating. Some schools were open when they should have been closed; others were closed when they should have been open. Parents have horror stories of their kids (some, then all, then others) having to stay home for weeks at a time because one or another member of the household tested positive or was a close contact of someone else who did. And we know the consequences for students who didn’t have access to in-person school have been significant.

All this to say, “stay home; save lives,” which I, and others on the left, advocated for should never have been a long-term solution. The costs were extremely high. But as a short-term measure to prevent hundreds of thousands of deaths, it seemed like a good trade.

Red America De-Commits from Shared Responsibility

The first change in the situation came when red America decommitted from any serious attempt at virus mitigation. Despite cases coming down while testing ramped up in May of 2020, Republican governors proudly announced that they were ending mitigation efforts (usually the cessation of mask mandates and shutdowns of some indoor venues) and returning to normal with a “mission accomplished” sort of message. As if chest-beating displays of aggression and defiance have any impact on a virus…

The result was a scenario where it didn’t matter how much blue America tried, COVID-traceable became impossible. When 1/3rd of the country takes few measures to mitigate the spread of something as transmissible as COVID, it will just be around. It doesn’t matter what the remaining 2/3rds of people do.

But this didn’t change the behavior of or calculus for blue America. In a pre-vaccine world with COVID running rampant, “stay home; save lives” was still an ethnically valid mantra. But the timeline elongated from “until we reach COVID-traceable” to “until we get vaccines.”

In addition to driving up the costs by elongating the timeline for some easing of isolation, red-America’s de-commitment from shared responsibility killed hundreds of thousands of people. Here, I am just talking about the period after the initial wave and before vaccines were widely available.

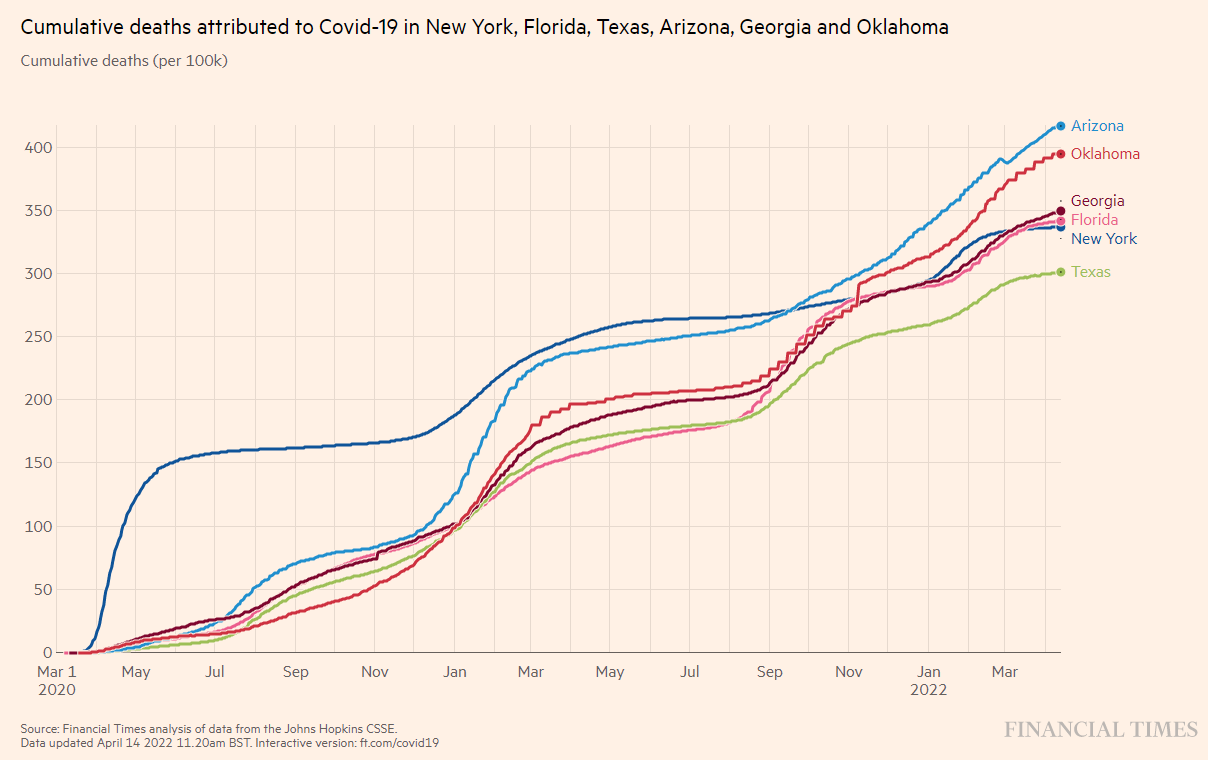

This chart is the most damning indictment I can imagine of the US’s response to the pandemic from the end of April, 2020 on. What you are looking at is the cumulative excess death rate – in other words, how many more deaths happened in different countries relative to the number they would have expected absent COVID, expressed as a percentage. If, in a given week, a country was forecast to experience 10 deaths, and it experienced 11, this would show a result of 10%.

What we should see, for most countries, is this number coming down over time1. At the beginning of the pandemic, we didn’t know anything! We didn’t know how the virus spread, how to stop it from spreading, how to treat infected patients, etc. As time went on, we got more information about that. Each subsequent wave might temporarily drive this number up again, but in general, the trendline should be down.

That’s what we see for Spain. That’s what we mostly see for Italy, with a wave in the fall of 2020. It’s what we see for the UK, with a wave hitting in the winter of 2020-2021. France is largely flat, but at a much lower level, with one wave evident coincident with the one in Italy.

The US is the opposite. At the end of April, the US had clearly experienced many excess deaths, much of those concentrated in New York and New Jersey. But we were still doing far better than other countries with bad early outbreaks like Spain, Italy, and the UK. But from here, the line goes steadily up. As time went on, more and more additional Americans were dying.

Expressed in nominal deaths, the previous chart looks like this:

If we had merely followed the trajectory of France in the first chart, 300,000 more people would not have died between April 26, 2020 and February 14, 2021. This is largely the fault of Republican governors and Fox News for suggesting that people ought to just get about their business rather than continue to stay home and always wear a mask when going indoors with others.

Unfortunately, red America’s decommitment from mitigation measures like staying home and mask-wearing proved the point that the rest of us were right to engage in these stringent mitigation efforts. We have the counterfactual staring us in the face, and it’s the possible prevention of 300,000 premature deaths.

Vaccines Changed the Situation Again

The welcome availability of vaccines in the first half of 2021 meant that by the summer of that year, anyone who wanted a vaccine could get one. Yes, there were (and remain) issues of access and availability, but if you really wanted a vaccine, one would have been available to you.

The insertion of human choice into the equation of about the effects of disease transmission inherently changes the moral responsibility we have for disease transmission. If people can choose to protect themselves, then we are not each entirely responsible for the health of others.

This change of circumstances has seemingly divided the left. The center left is comfortable with the notion that vaccines are a choice which people should make to protect themselves, and if they don’t choose to protect themselves, we don’t owe them significant sacrifices. The hard left points to the people who can’t, for whatever reason, get the vaccine, or people for whom the vaccine’s protection may prove insufficient, as evidence that we are still responsible for the health and well-being of others.

There’s still some middle ground. We should still wear masks in many public indoor settings (there’s no reason not to!). We should still stay home when symptomatic, even if we test negative (since sometimes the rapid tests are producing negative results despite early symptom onset). But we shouldn’t not go anywhere or do anything when cases are low simply because some people remain at risk of severe infection and we might be unwittingly spreading the disease.

The discourse is still focused on personal choices when it should be focused on policy

While I often side with the hard left when it and the center left come into contact, it’s unclear to me exactly what sorts of behavior-change the hard left is advocating at this point. Should we not go to the theater (that requires masks) for the sake of others? Should we not visit with friends and family in their homes? Which behaviors, exactly, should we sacrifice? There’s no clear rule-of-thumb to me here. It’s all conditional.

The availability of vaccines has, in my view, shifted the burden of proof toward the left. Pre-vaccines, the right should have been advocating thresholds of cases or test-positivity below which some in-person activities should have been allowed to resume. Now that vaccines are available, I think it’s incumbent on the left to identify a threshold above which some activities ought to be suspended. The idea that with rolling waves of infection we might re-impose certain mitigation efforts makes sense, but these should be used sparingly and the gating criteria for reimposing such measures should be clear.

Increasingly, the mitigation-advocates I see have an element of hysteria about them: “there’s a new variant”; “50% of cases result in long COVID”; “I guess we’re just willing to accept hundreds of thousands of excess deaths now”; etc.2

Decrying that “people are acting like the pandemic is over” is both unspecific and counterproductive. The situation has changed. Our behavior should too. We sacrificed a lot in our effort to minimize the number of deaths in a world without vaccines. Now that there are vaccines, we don’t all bear collective responsibility for how the disease is transmitted.

An example: I love going to cafes. They are great. I have often written Bloom Briefings from cafes. But I stopped during the pandemic. Cafes are very conducive to the spread of disease. But I go to cafes again now. I am vaccinated and boosted. My risk is low. And if I somehow contract the disease without symptoms and I’m spewing COVID around everywhere in the café, the other people in the café have assumed the risk of that possibility when they chose to go to the café. I’m not sure there’s anything I could do differently that would make a café safer for an immuno-compromised person. I don’t think I should not go to cafes because there are still COVID cases.

But cafes are also pure gravy, so to speak. There’s nothing necessary about them. I could buy coffee and make it at home. But I find enjoyment, inspiration, fraternité, in being at a café among the people. My life is richer for going to cafes. If other people aren’t willing to get a vaccine, why should I stop going to cafes?

At the same time, the center left seems more intent on scolding the (in their eyes) overly-cautious than building good policy. Here, Nate Silver mocks a woman for figuring out the safest way to meet a friend indoors (in a city with low case counts at a café that checks vaccinations). This, too, is totally counterproductive. We still have to make decisions about when it’s safe to do things and when it’s not!

Lena Wen, another “get back to normal” advocate, frames how we ought to act particularly badly here: “Our calculation for deciding which events to attend isn’t based on the risk of each event but, rather, reflects the point we have reached: We are no longer prioritizing avoiding the virus over living our lives.” It’s not one or the other! We should do both! Balancing the two together. As we have been the whole time!

Both the center-left and the hard-left need to stop fighting over what individuals should be doing (people are going to make their own choices based on their own risks and priorities) and spend more time devising smart mitigation policies that help people live their lives to the greatest extent possible while still preventing massive numbers of hospitalizations and deaths.

The left has had better proposals than the right for how to proceed throughout the pandemic, but this mode of discourse from both factions of the left is deeply unhelpful. Should governments be doing more? Yes. Should we be trying to help people do more of the activities they did before COVID? Yes. But this means government taking measures to help protect people as they resume more and more aspects of their pre-COVID lives.

We each have to balance the risk of contracting the disease and spreading it to others we love and decide if we are comfortable accepting that risk in order to do things we enjoy. Do you want to go to that concert? Do you want to go to a bar or restaurant? While you no longer have a collective social obligation not to do these things, you still have decisions of personal risk to make. And the focus of our COVID discourse at this point ought to be helping make us feel more comfortable going out in the world and doing things. And we do that by making those activities safer.

What We Should Be Focused on Now

Our ability to go about our lives, the “return to normal” if you will, still requires some mitigation efforts. It makes sense to require some low-cost actions from people to stop the virus from spreading if that means more people can go about more of their pre-pandemic lives.

These policies, insofar as they related to individual behavior will have to be calibrated to three things:

The amount of risk mitigated by the measure

The cost of taking the mitigation measure

The political reality in the place where the policy is to be implemented.

But there are plenty of policies that aren’t human behavior-related. The first four policy suggestions here have nothing to do with asking people to change their behavior.

Paid Sick-Leave

Throughout the pandemic, but with much greater frequency in the last year, there have been many stories of employees being forced to work while sick because they don’t have sick leave, and the emergency sick leave passed in the initial pandemic package in early 2020 has expired. Employees need protection from having to go to work with COVID-infected co-workers, and you and I need protection from having to interact with COVID-infected employees at work.

There is no reason why this should be limited to COVID. We want the same protections from colds and the flu as we want from COVID. Those diseases also kill lots of people. A significant increase in protections for sick employees is needed as a matter of public health.

Make Tests and Masks More Widely Available

The federal government provided each household with up to 8 rapid tests. This is… totally insufficient. If people are to manage their own risk, they need to be able to test frequently. For the particularly cautious or the immuno-compromised, they may insist on someone testing negative before socializing with that person indoors. For most people, testing when symptomatic is a bare minimum. But we need rapid tests, and we need them to be free.

I would say the same about masks. If your employer wants you to return to an office, they should provide high-quality masks. You forgot your mask today? No problem. Your mask broke? No problem. Just take one from our supply. The government should also be sending people free high-quality masks at regular intervals.

Fund Research into long-COVID

The government needs to fund significantly more research into long-COVID. The biggest unknown on the risk side of things at this point is what the long-term effects of COVID-infection are. What are they? How frequent are they? Do vaccines mitigate the risk of these effects? How long do the effects last? We don’t have good answers to these questions, and to the extent that vaccines have shifted the calculus such that individuals are more responsible for their own risk, we need this information to be able to judge risk better.

Maintain Quarantine and Isolation Facilities

The government should operate voluntary quarantine and isolation facilities for people who are worried about exposing co-habitants. If you live with someone who is immuno-compromised and you become infected, you or they may well want to leave your residence to reduce the risk of transmission. Many people don’t have anywhere to go. The government should provide such facilities.

Vaccination requirement for indoor dining.

There is no reason why progressive jurisdictions cannot implement a vaccination requirement for indoor dining. Some American cities have had (still have?) such policies. The value here is that places where one is indoors, talking, unmasked are the most dangerous places for the spread of the virus. Restaurants are such spaces. So the amount of risk mitigated is reasonably high. The cost is low (and serves as an incentive for the reluctant to get vaccinated). And such policies would be supported in some jurisdictions.

In less progressive jurisdictions, individual restaurants should consider this. First, it would protect their employees from exposure. Second, even in purple jurisdictions there are plenty of people who would be happy for the extra security of knowing all their fellow diners have been vaccinated.

Masking in indoor congregate settings.

Sometimes, masks ought to be required in indoor congregate settings. The same rules apply. Here, the cost is the importance and joy of seeing other people’s faces and the discomfort that comes from a long time wearing a mask. The amount of risk mitigated here, though, is highly contingent on the spread of the virus. If there is a lot of COVID around, then there should be more mask requirements. If there is less COVID, in some settings, the requirement may be removed.

Conclusion

We aren’t likely to ever live in post-COVID world. It’s here to stay. And while it’s naïve to think that we should attempt to return to our lives exactly as they were in a pre-COVID world, we ought to strive to do as many of the things that brought us joy and meaning and fulfilment before COVID as possible.

Yes, this includes going to restaurants, attending parities, celebrating achievements at banquets, cheering our sports teams on in indoor arenas, getting swept away in music at concerts while co-emoting with 1,000s of our fellow humans, and many more activities that require taking on some risk of contracting COVID.

These activities, however, ought to be undertaken judiciously. We might opt out of some or all of them if case counts are high in our area, or if we are planning to visit someone at high-risk of negative COVID outcomes soon. But we can no longer operate in a world where it’s assumed that doing these activities is inherently bad.

At this point, the left’s goals ought to be, as they often are in other areas, implementing policies that will make us all better able to enjoy our lives to the greatest extent possible. I don’t believe visiting opprobrium on those people who still refuse to get vaccinated will accomplish much. And the case for scolding people for going to bars or restaurants or on vacation is even worse.

But we can and should press government and sub-governmental institutions to implement policies that will help us better manage our own risk. We need more tools to protect ourselves, and we need the government to protect us from unscrupulous institutions that will put their profit above sensible measures for the good of public health.

Life is simply more complicated now. Decisions that were once easy are now harder. The answer isn’t an unthinking return to everything we did before, nor is it perpetual isolation. We have to continuously evaluate risks and trade-offs. It’s tiring, but if we ever need a break from this constant evaluation, the outdoors remains extremely safe (from COVID). We can always enjoy the local park.

Thank you.