One Year of the Pandemic

Bloom Briefing 50: Governmental Failures Leave us Exposed and Alone

During the week when our lives changed forever, on March 10, 2020, I left work early to pick up some new dress shirts. I joked with the salesman that this counted as stocking up on essential goods as if in preparation for a blizzard. That night is the last time I ate at a restaurant. As I left work on March 11, not even my most pessimistic outlook on the future included the eventual reality that I wouldn’t see almost any of my coworkers in person for the next year.

That total lack of preparedness—one which has persisted throughout the entirety of the pandemic—is the direct result of institutional failures. Our governments have abandoned us. They have left us high and dry, without the infrastructure required to stem the spread of the disease and without the information or guidance we need to know how to protect ourselves and others.

We were thrown into this vortex of disease, death, chaos, and loss and left to fend for ourselves. We have searched out information from those we felt were credible. We have adapted our behavior based on anecdotes and advice from friends. We made masks, then bought masks, then doubled-up masks, then upgraded masks—or disregarded masks entirely—based on this word-of-mouth and anecdotal evidence. We have made decisions about whether or not to visit family members and whether to send our kids to school not knowing if we are taking a minor risk or a major one. Grocery store workers and janitorial staff, doctors and nurses, bus drivers and food service employees have continued to show up to work, making hundreds of decisions every day that affect their entire family’s risk of contracting the disease, all without half-decent information about what actually matters.

Beginning in February last year and continuing to this day, four systemic failures of government set us on a bad course from which we could not deviate. First, the goals of the early lockdowns were ambiguous. Second, government failed to stand up a system of testing, contact tracing, and isolation with adequate speed (contact tracing and isolation remain spotty, though testing has gotten much better). Third, the advice around masks and how to protect oneself from disease was wrong. And fourth, the phased re-openings and re-closings have had only tenuous connection to anything resembling scientific justification.

The short-term result of each of these failures has been individuals picking up the slack, figuring out on our own what is safe and what isn’t. The long-term consequence of this failure of government will be enduring skepticism about its competence and utility.

Bad Advice on Social Distancing

On March 12, I started working from home. Why were we staying at home? Just because? To buy the healthcare system time to procure PPE and build out capacity to treat COVID patients? To buy the government time to set up a test-trace-isolate system? To reduce the number of infections? To reduce the number of deaths? Until there was a vaccine? It was never clear and there was never agreement.

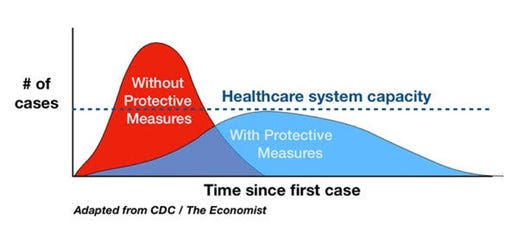

Let’s start with “flatten the curve,” which is a term many people—myself included—learned for the first time in March. By now you’ve all seen an image like this one:

As the graphic suggests, the basic premise of “flattening the curve” is to buy the healthcare system time. If the same number of infections occurs over a longer time horizon, the risk of the healthcare system being overwhelmed is significantly reduced.

If one took the goal as ensuring hospital and healthcare system capacity, the lockdowns mostly worked. Only in isolated geographies and for brief periods have hospitals been overwhelmed. But many people didn’t realize people staying at home was working. As daily testing increased throughout April and May, the number of confirmed cases per day declined slowly. What public health experts knew to be true – that this meant there had been a much larger number of untested positive cases in March and early April – didn’t filter through to the American public, who understandably took the anemic progress towards stamping out the disease as evidence that the lockdowns were barely having an impact. After all, the “flatten the curve” graphics all show cases eventually subsiding, and that just wasn’t really happening at anything like the rate depicted in the graphics.

But ensuring hospital and healthcare system capacity isn’t the only goal of flattening the curve. Unfortunately, the translation of the above graphic from CDC paper to public consumption left out the ultimate goal. The New York Times actually documented the history of this graphic without noticing one particular change. The original graphic looks like this:

Importantly, this graphic has “reduce number of overall cases and health effects” as a goal. In the vast number of images you will find with a Google search or on the major media websites, few will include this essential reason for flattening the curve. The purpose of all our mitigation strategies is to reduce long-term health effects and death. One part of that is ensuring hospital capacity; another is minimizing the total number of cases.

The lack of consensus around the purpose of the lockdowns created an impossible tension. If you thought, in March or April or May, that the goal of the stay-at-home orders was to seriously bring down the number of cases, you might have been trying to reduce your risk to zero. Meanwhile, lots of other people, including many political leaders, seemed to operate with the goal of getting things back open again as quickly as possible. This meant that, no matter how hard you tried, you were no longer part of a collective effort to stamp out the disease because… there was no collective effort to try and stamp out the disease. You were simply protecting yourself. But government couldn’t help you do that effectively either.

No Effective Test-Trace-Isolate System

In the early days of the pandemic, one of the stated goals of flattening the curve (again, with the end aim of reducing death) was to buy the government time to increase testing capacity and organize a system for how to identify and quarantine/isolate people who had been exposed/infected.

One feature of COVID that makes it so difficult for us to deal with is the fact that people without symptoms can spread the disease. This happens in two ways. First, people who never develop symptoms (asymptomatic cases) can still infect others. Second, people who will eventually develop symptoms are most infectious before they start feeling sick. This graphic from MIT’s Medical School is helpful:

What this means is that if you want to prevent people from spreading the disease, you actually need to identify them as having been infected before they would experience symptoms. This is why contact tracing is both important and challenging. When one person tests positive, contact tracing allows public health entities to identify the people that person may have infected before they begin to infect others. Scientists estimate that infectiousness begins 2-3 days after exposure.

So imagine I am exposed (and the journey of my infection begins) on Monday. I see you on Thursday. I’m probably infectious, but I don’t know it yet because my symptoms won’t begin until Saturday. I show up at a health facility on Sunday and get a COVID test. (Delays in getting results at times have seriously hindered contact tracing but are better now.) On Monday it’s confirmed that I’m COVID-positive. This means you were exposed on Thursday, but it’s Monday. You’re already infectious. Even if contact tracers are in touch with me on Monday, they probably don’t get to contact you until Tuesday, in which case, anyone you’ve been in contact with since Sunday has been exposed.

You can see how, with people who work together regularly—say, a baseball team—contact tracing simply won’t work. By the time you know someone has been infected, it’s very likely many people have been infected (unless there were other mitigation measures adhered to with some rigor). But for the rest of us, it could work okay – we don’t have quite so many overlapping contacts. It would just have to look different than how it looks here (which is basically non-existent).

In Vietnam, the non-island nation that has best-controlled the spread of COVID, contact tracers identify contacts up to four degrees of separation from the index case. Close contacts who test negative quarantine at a government-run facility for two weeks. Close contacts of those close contacts quarantine at home for two weeks. You can (and should) read more about Vietnam’s success story here.

The US didn’t try to do the trace-isolate part of the test-trace-isolate model at scale. Some specific geographies have created more robust contact tracing teams, but our approach to mitigating community transmission is basically limited to masking (more on that in a minute). When community transmission is high (as it has been in most parts of the US since the summer), contact tracers are overwhelmed.

Furthermore, some people don’t want to divulge their close contacts. Other people can’t be reached. Some close contacts won’t quarantine even when alerted to the fact that they have been exposed. While some state or local public health agencies have created spaces (and are paying for) for quarantine and isolation, these tend to be opt-in rather than compulsory. And mixed paid sick leave policies (good luck figuring out whether you are eligible and how to get money from this, the government’s supposed remedy) have meant that some people who know that they are infectious or have been exposed simply cannot afford to take time off of work.

The complete failure to stand up systems to comprehensively deal with infections has meant that burden has fallen to each of us individually to estimate our risk of exposure and contraction. What counts as exposure? Let’s say you gathered outside with six friends in a socially distant way without masks (you were eating or drinking). The day after, one of those people tells you they were exposed (indoors, no masks) four days earlier by a visiting family member who has now tested positive. Instead of your local public health agency telling you how to handle this situation, you are left to estimate your own risk of exposure. Is it enough to cause you to quarantine? What about the people you live with? Do you go to the grocery store? Or go for a masked walk with a friend outdoors?

Two of the six friends at the get-together decide it’s unlikely they have been exposed. You’re more cautious. They’re doing things you wish you could do but feel irresponsible doing. Now you’re resentful of your friends, but you don’t know if you should be or not. Maybe they’re behaving perfectly rationally and a functioning government public health agency would have told you not to worry about it. But also maybe they are being irresponsible. Should you tell them?

As individuals we are ill-equipped to deal with this sort of decision-making. It requires expertise in disease transmission, public health, and moral philosophy. I spent months reading about the former two for work and studied the latter in college and grad school, and I still feel very little confidence in my answers to these questions. And as challenging as it is to determine the right course of action in the scenario above, it’s a reasonably easy scenario! It doesn’t involve any of the economic trade-offs associated with having to work in-person.

Bad advice about masking and disease transmission

It can be difficult to think back to the first weeks of the pandemic, but in those first weeks, the CDC’s advice was still against wearing masks. It wasn’t until early April that the recommendation changed so as to encourage mask-wearing in public. (The CDC’s advice against widespread masking is preserved here.)

This was all despite the fact, as we know now, that the government—and Trump himself—knew as early as the first week of February that the disease was transmitted through the air. WHO’s advice lagged the US’s when it came to masking, but the evidence was clear: countries with stronger cultures of masking (specifically South Korea, Taiwan, and China) were seeing significantly less transmission.

It’s unclear how much this lie was precipitated by a fear of a run on masks, which were in short supply where they were needed most (at hospitals treating COVID patients), versus a genuine lack of understanding about the airborne spread of the disease, but the damage was done. Inconsistent guidance on masks left the door open for the most important weapon in our arsenal of COVID-19 mitigation strategies to become a political lightning rod.

As more (mostly blue) states enacted ordinances requiring masks be worn indoors, some folks protested by refusing, shouting at employees, and even occasionally engaging in violence. This abuse of employees attempting to enforce COVID-19 mitigation measures in their workplaces became such a common phenomenon that the CDC actually published guidelines titled, “Limiting Workplace Violence Associated with COVID-19 Prevention Policies.”

The anti-mask persuasion in American life continues to be a way—for reasons I genuinely find difficult to explain—for revanchist right-wingers to stick a finger in the eye of people who would like to be protected from COVID infections. This is why, despite obvious signs the UK variant is on the upswing here right now, Texas, Montana, Iowa, North Dakota, and Mississippi have all lifted their mask requirements.

The same phenomenon that played out with masking—in which public health officials lied to the public in order, theoretically, to prevent a run on masks—played out to a lesser extent with social distancing. The reality about six-foot distancing is that six feet is a made-up number, “based on an outdated, dichotomous notion of respiratory droplet size” (source). Your risk of contraction isn’t seriously high at five feet and non-existent at six feet. Distance decreases risk, but so do other factors.

While the early advice around methods of contamination focused on surface contamination (a study revealing the length of time COVID could remain living on different surfaces garnered days of alarming press coverage), by late spring, the science was very clear that airborne transmission (breathing the air an infectious person had exhaled including some infectious particles) was the more common means of infection.

Risk is a function of not just 1) proximity to an infectious person, but also 2) the length of that exposure, 3) the volume of air in the space where you were exposed, 4) the quality of the air circulation in said space, and 5) how many infectious particles that person is shedding. The last of these is, itself, a function of the point in the COVID lifecycle of the infectious person, how hard the person is breathing, and how much masking reduces the number of infectious particles emitted.

The six-foot guidance was helpful for a number of things: taping checkout aisles at grocery stores or other queueing spots, as a general rule of thumb for proximity with those not in one’s household, etc. But because it wasn’t accompanied by a full picture of how the disease infects others, some people believed that if they never got within six feet of others, masking wasn’t required.

The guidance around physical distancing still operates with this standard six-foot-at-all-times credo that just doesn’t carry a lot of scientific basis. Six feet won’t protect you in a tiny gym with unmasked people working out. And if you were outdoors shouting at protests while wearing masks, the lack of six-foot distancing seems not to have mattered.

I could understand some skepticism about the thesis that the oversimplification around six-foot physical distancing was a problem, per se. But by giving people a narrow view of what mattered and what didn’t when it came to transmission, the six-foot guidance has given lots of people a bad understanding of the risks of certain situations. That’s bad enough if it’s you or me getting together with friends or going to the store, but what about when it’s local political leaders deciding what sorts of venues can be open at what capacities with what sort of physical distancing guidelines? As we attempted (and are continuing to attempt) to open back up different kinds of congregate spaces like stadiums, theaters, and schools, how we efficiently adapt those spaces to reduce risk hinges on what amount of distancing is necessary.

Lack of Standard Gating Criteria for Reopening Leads Local Politicians to Make Bad Decisions

As the first wave of cases began to subside in April and May, many of us were looking for guidance around what levels of progress would lead to the relaxing of certain stay-at-home criteria. One would think that establishing “gating criteria” on a population-controlled basis (e.g., restaurants can open at 25% capacity for in-person dining with fewer than 10 new cases per 100,000 people per day) would have been the purview of the CDC, but they never produced clear guidance of that sort. The only guidance along these lines was that states should have a “downward trajectory” of either confirmed cases or percent of tests positive.

Other entities filled the void left by the CDC. My personal favorites were the PRAM dashboards of the University of Nebraska Medical Center (which were specific to the state of Nebraska) and the optimistically-named website, CovidExitStrategy (now COVID Act Now). Each of these attempted to identify the important metrics and establish green-yellow-red (or additionally-tiered) thresholds for how safe a state (or region) was at that moment.

But these entities were not public health agencies, and public health agencies didn’t always make decisions that aligned with the mission of protecting public health. Many states (more red than blue but not exclusively so) seemed to make decisions to reopen lots of entities with few restrictions in a way that nearly seemed to ask for rampant spread of disease. As this New York Timesarticle from May notes, many states were reopening without meeting even the loosest guidance (downward trajectory) prescribed by the CDC.

When local public health agencies did try to fill this void, they were summarily ignored by local politicians. Even in the science-loving Democratic bastion of Washington, D.C., the phased reopening began before the gating criteria delineated by DC’s Department of Public Health had been met. While the CDC was meekly suggesting that people minimize non-essential travel, chambers of commerce and business associations were lobbying states to ease stay-at-home and social distancing requirements in advance of the summer tourism season.

By early June, there was reason for optimism. Nationally we had seen declining daily cases at the same time as testing was ramping up. Nurses that had gone to New York to help with the first wave of cases there returned home. And people looked forward to putting the worst of the pandemic behind us. If you’re a forgiving or charitable person, maybe you feel this false dawn let us take our eye off the ball or gave us a false sense of security. Given our political failures throughout the duration of the pandemic, I’m not inclined to be so generous.

For both pedagogical and economic reasons, elementary schools are the single most important institutions to ensure operate in-person. Elementary school students need the in-person learning and socialization that happens at school. And their parents need the childcare that elementary schools provide.

The debates around school reopenings are fierce and ongoing, and I feel a great sense of ambivalence. I have a strong opinion that strong opinions about school reopening are almost all misguided. It was the most important institution to get right, but for a confluence of reasons, we often failed. Schools were closed because state public health agencies had guidance from the CDC that was impractical (six-foot physical distancing), because school districts had an unclear understanding of how to minimize risks, because teachers’ unions had bad guidance about the risk to teachers, because the teachers’ unions made impractical demands, because governments prioritized opening things like restaurants and bars and gyms that mean community transmission remained high, and because, individually, lots of parents feared for their students’ safety if their students attended in person… because those individuals had good reason to distrust the politicians saying schools were safe to open… because those politicians clearly didn’t have a coherent framework for understanding the risk of transmission and were clearly not prioritizing public health in plans to reopen.

In isolation, the failure to get all young students to school in person isn’t the worst failing of our governments. Washington, D.C., opened restaurants for indoor dining before playgrounds. The United Kingdom went so far as to subsidize people eating in restaurants—the “Eat Out to Help Out” scheme—that likely contributed to a significant increase in cases there. Nor is the failure to get students to school in person as purely evil as lying about the number of deaths in nursing homes or persecuting a former lead public health researcher as Governors Andrew Cuomo and Ron DeSantis have done respectively. But the consequences of the failure to get all students to in-person elementary school have been more severe. On an economic front, women’s participation in the labor force has fallen to a rate last seen in the 1980s. On an education front, millions of students have simply been missing from school.

As with advice around masking, as with the rules around social distancing, as with the failure to stand up a test-trace-isolate system, our governments failed us with reopening. They prioritized getting the wrong things open. They prioritized opening over safety, even when case counts were high. And they often failed to deliver on opening the most important institutions: elementary schools.

This put all of us in one of two impossible positions. If your school was in-person, you had to decide whether the conditions at that school would keep your children—and consequently you, yourself—safe. If your school was remote, you had to decide whether A) you were going to strive for some stress-inducing trifecta of being employee, parent, and teacher, B) you were going to take time off from work (if you could even afford to) to spend more time supervising Zoom-school, or C) you were going to find some alternative means of getting your children in person learning via private school, pandemic pods, or home-schooling. God forbid your school was in some hybrid learning environment and you had to evaluate both sets of challenging trade-offs.

Conclusion

None of the preceding should minimize the heroic work of the thousands of people at public health agencies across the country who have been working in good faith to try to mitigate the worst consequences of the pandemic. These workers have put in long hours that have done a lot of good, often in near-total obscurity.

Too often, these public servants have been ignored, whether for the sake of political posturing (e.g., states not enacting the most basic of mitigation measures), naked corruption (e.g., New York), or some combination of general incompetence mixed with either of the other two. For the country with—theoretically at least—the world’s preeminent public health agency, this is a shocking failure that continues at present with opaque logic around vaccine distribution and Kafkaesque protocols for securing an appointment.

As the federal government, state governments, state public health agencies, and local public health agencies all fail to provide adequate guidance to help us through the most challenging year most of us have ever experienced, we have been left to make life-and-death decisions based on whatever guidance we could find.

How do we see friends in person because we’re in desperate need of social contact? How do we safely arrange for the plumber to come fix the pipes? Do we correct him if his mask slips? Do we send our kids to in-person school even though we’re not sure it’s safe? Do we take time off of work to teach home-school? Are we comfortable having groceries delivered knowing that we are simply paying to outsource the risk of contracting disease? Is it safe to go to work? How could I or should I make it safer? Do we visit an ailing family member? Can we negotiate agreed precautions with an extended family before gathering for a holiday? Do we hold an in-person wake or memorial service?

These decisions are made upon the animate Harry Potter chessboard: one wrong move could very easily result in death. That death might be yours or you might unwittingly set off a cascade of infections that results in dozens of deaths. And you have to make these decisions with bad information about how the disease is spread and with insufficient guidance from the agencies that are supposed to help you limit the spread. To make these choices still harder, you must make them with the knowledge that even zero-risk behavior on your part won’t retard the tsunami of death washing over the country because millions of your fellow countrymen have decided it is fine if 100,000s of people die.

We aren’t accustomed to making decisions with this amount of moral consequence on a routine basis. So we either minimize the number of decisions by living hermit-like existences, deny the seriousness of the decisions, carry the weight of them around with us like leaden weights strapped to the end of yokes across our shoulders, or succumb to the ghost of nihilism whispering in our ear.

I am not suggesting that the federal government could have prevented a mass-casualty event. The countries that have COVID death counts orders of magnitude smaller than ours have irreplicable advantages (i.e., no land borders) the US does not. A quick tour of Western Europe does not reveal a country that is emerging unscathed from the pandemic. That the US (160) has exceeded the death rates per 100,000 population of France (132), Switzerland (118), Netherlands (92), and Germany (87) suggests that our political failures have had deadly consequences. If the US had even France’s death rate, 90,000 more people would still be alive. With Germany’s, that number would be 240,000.

The vaccine is coming to save us, but not in time for the half-million souls who have perished. The vaccine will not rejuvenate us from the exhaustion of making thousands of moral decisions, from the guilt of potentially transmitting the disease, or from the failure of our democracy. The vaccine may save us from COVID, but it will not fill the empty chairs at our christenings, graduations, and weddings. It will not give us back the year we have lost.

It will be a good summer. Those of us who want vaccines will be able to get them by then. It will be easy to gather outdoors where risk is reduced. And the natural seasonality of COVID means transmission will naturally decline anyway. The future beyond remains unclear. Until such a time as we feel confident in our safety, likely sometime between being vaccinated and reaching herd immunity, we beat on, solitary boats against the current.

Additional Reading (in case the 4,500 preceding words have left you wanting more)

At The Atlantic, Ed Yong has written too many fine pandemic pieces to count. His profile of the long-haulers—those who suffer symptoms for months—is particularly good. His look-ahead to year two of the pandemic (published in December) remains timely.

For the New Yorker, Lawrence Wright chronicled the year that was in one of the magazine’s longest-ever pieces, “The Plague Year.”

Writing last May for ProPublica, Joe Sexton and Joaquin Sapien documented the different approaches San Francisco and New York City took to the pandemic, and how New York’s governmental incompetence—including infighting between Cuomo and DeBlasio—undermined efforts to protect citizens’ health.

On Substack, Zeynep Tufekci wrote about how our mental models for vaccine effectiveness are wrong, and why you should get whatever vaccine you can.