Chauvin Guilty; European Super League

Bloom Briefing 57: Justice for George Floyd; Avarice Gets its Comeuppance

The Bloom Briefing this week focuses on the the guilty verdict returned in the trial of Derek Chauvin for the murder of George Floyd and the launch and abortion of the European Super League.

Justice for George Floyd

The jury in the trial of Derek Chauvin returned a “guilty on all counts” verdict few of us dared to hope for, even if it seemed the only possible conclusion from the facts presented at the trial. Relief is the prevailing emotion. The least worst outcome from a terrible situation was achieved.

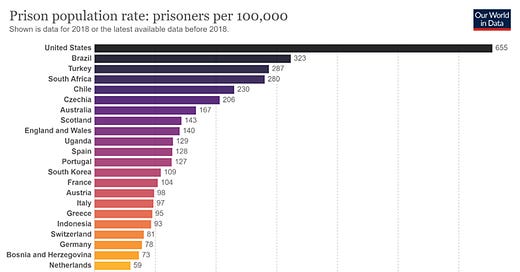

It is not a good thing to lock anyone up for the rest of his life. The penal system is America’s most comprehensive system for denying people freedom. It exploits not only those locked inside, but their friends and families as well. Private prisons (which shouldn’t exist) are simply a mechanism for graft, funneling billions of dollars of government contracts to the prison industrial complex, whose leaders in turn fund the campaigns of the politicians giving them the contracts. Sometimes this even involves direct kickbacks! The system is wildly racist. Incarceration shows basically no evidence of preventing recidivism. And the US’s incarceration stands alone among the liberal democracies of the world:

Despite all this, Derek Chauvin deserves to go to jail. He suffocated the life out of another human over the course of nine-and-a-half minutes while that man—George Floyd—begged for his life. It was a crime of inhuman brutality, only capable of being done, one feels, to someone Chauvin didn’t deem fully human. So the murder, captured on video for the whole world to see, became layered with the symbolism of the long of history of racist policing in America.

But the exceptional brutality of Chauvin’s murder of George Floyd also leaves plenty of room for skepticism about whether a corner has actually been turned regarding accountability for police violence against unarmed (disproportionately Black) people. In the more typical (how awful it is to use that adjective) killings involving a police officer shooting someone, will we ever see any justice? There was no justice for Philando Castille or Tamir Rice or Breonna Taylor or Antwon Rose or Stephon Clark.

Even the cases of exceptional shootings haven’t yielded guilty verdicts. The police officer says he’s “gonna kill this motherfucker” before doing so, as in the shooting of Anthony Lamar Smith? Not guilty. The police serve a no-knock warrant for a person who isn’t present before opening fire upon the residents who are there and asleep, as in the shooting of Breonna Taylor? A police officer admits to accidentally firing her gun instead of her taser, as in the shooting of Daunte Wright? Time will tell.

If there is reason to hope, it is perhaps the divergent outcomes in the six years between the similar killings of Eric Garner and George Floyd. Both men’s pleas that they were unable to breathe were captured on video while they were being held in prohibited chokeholds while posing no threat to police officers or the wider public. Daniel Pantaleo wasn’t even in charged in Eric Garner’s killing. Derek Chauvin was convicted on all counts.

European Super League Aborted

If you blinked this week, you might have missed the birth and death of the European Super League. Last Sunday, led by Real Madrid president Florentino Perez, 12 teams[1] announced that 15 teams[2] had agreed to participate in a European-level competition of football’s biggest clubs. By Tuesday, due to nearly universal opposition, including from fans of the clubs involved, plans for the Super League had been shelved.

To understand the unpopularity of the European Super League, it’s important to understand some key differences between European football and American sports. Unlike American sports, which are closed competitions, European football exists in an open environment. With promotion and relegation of the top and bottom teams in each level of competition in each country in Europe, theoretically at least, a club from the 9th tier of football could eventually reach the top.

Another key difference is that, for the best teams, there are two levels of competition. Teams compete in their domestic league every year, and the top (four, in the big leagues) teams qualify for the top European-level competition (the Champions League, as it’s currently called) in the next year. This means that spots in the most prestigious club competition in European football have to be earned.

Underlying the impetus for the European Super League is a desire for a greater share of very large sums of revenue from TV rights. The top clubs believe that if they play each other more regularly, they will be able to make more money than in the current setup of European competition (their proposal continued participation in domestic leagues).

Of course, these teams are already owned by billionaires (or billion-dollar conglomerates) and, with compensation based on performance in the tournament, take in a disproportionate share of Champions League revenue. Chelsea’s owner, Roman Abramovich, is estimated to have a net worth of $15B; Arsenal’s principal owner Stan Kroenke is estimated to have a net worth of roughly $8B; Fenway Sports Group (who own Liverpool) are valued at just under $8B; AC Milan are owned by Elliott Management Corporation, valued at roughly $41B; Manchester City are literally owned by a country—principal owner Sheikh Mansour is Deputy Prime Minister of the United Arab Emirates and a member of the royal family of Abu Dhabi.

The vast disparities in wealth make some of the fans’ protests about the closed nature of the European Super League seem oblivious to the current inequality of football. No team outside of the 15 proposed Super League members has even reached a Champions League final since 2004. It’s effectively already their competition with guest participants producing surprising runs to the quarter- or semi-finals every few years: Ajax in 2019, Bayer Leverkusen in 2020.

All of this raises questions about what makes sport good. Most of the things we value about sports involve trade-offs between competing goods. We want a balance between parity and some inequality. We want upset stories to root for (which requires some inequality), but we don’t want them to be too infrequent. We want to see the best players in the world, but we also want our teams to have local players. Even with the best football clubs being global brands with supporters around the world, we don’t want to totally give up the provincial feel of competition between teams in particular geographies.

The question we have to ask ourselves is to what extent the Super League would move us toward or away from these goods. In that context it seems abundantly clear that the Super League would exacerbate the already massive wealth gaps between the participating teams and the rest of their domestic leagues. This would be like American billionaires trying to form their own country in order to avoid various corporate and personal taxes because they thought the US wasn’t unequal enough.

Even if the goal were to make a full break with domestic competition and only play in the Super League (which it wasn’t), it would only serve to complete the transformation from idiosyncratic local football clubs to antiseptic international corporate brands. Just because that transformation was already 90% complete doesn’t mean we shouldn’t resist the remaining 10%. Fans already complain about the same cohort of teams always winning the Champions League. Even with five slots reserved for qualifiers from domestic leagues, would those teams be able to compete with the enhanced financial firepower of the teams in a Super League?

The Super League will always appeal to the rich clubs because exchanging games against Burnley and Elche for games against Bayern Munich and Juventus will always present an opportunity to make even more money. And football’s billionaire owners didn’t get to be billionaire owners by passing up opportunities for more money. But this week proved that fans, united in opposition, do serve as a democratic check on the most obviously ingordigious interests at the top of the game.

Additional Reading:

At the Atlantic, Adam Serwer wrote about white supremacy is embedded into policing’s history.

At the New Yorker, Editor David Remnick interviewed staff writer Jelani Cobb about the guilty verdict.

[1] Real Madrid, Barcelona, Atletico Madrid, Manchester City, Manchester United, Liverpool, Tottenham, Arsenal, Chelsea, Juventus, AC Milan, Inter Milan.

[2] The Super League teams thought Bayern Munich, Borussia Dortmund, and Paris Saint-Germain would participate too, but those clubs pulled out before it was even announced.